Lépjen offline állapotba az Player FM alkalmazással!

Meet the Plants! SF Botanical Garden Looks Like Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory for Flora

Manage episode 273561361 series 2486058

Stepping onto the 55-acre grounds of the San Francisco Botanical Garden feels a bit like entering the chocolate room at Willy Wonka’s factory, if that storybook setting were bursting with real plants instead of ones made of candy.

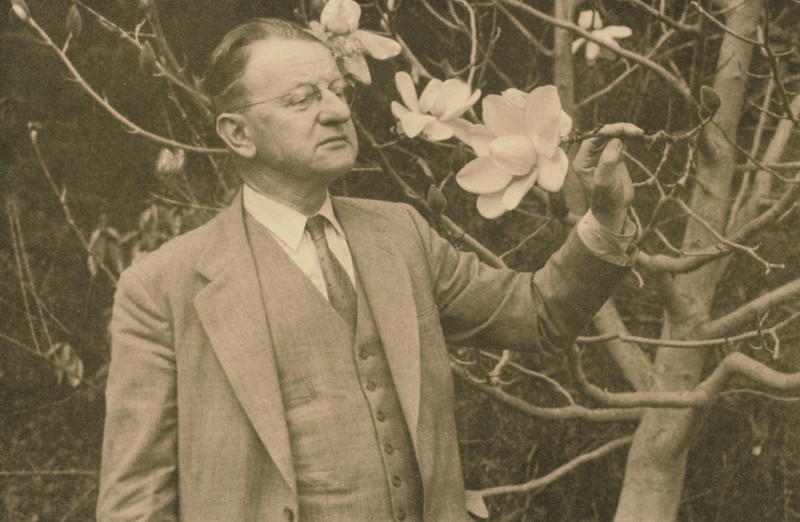

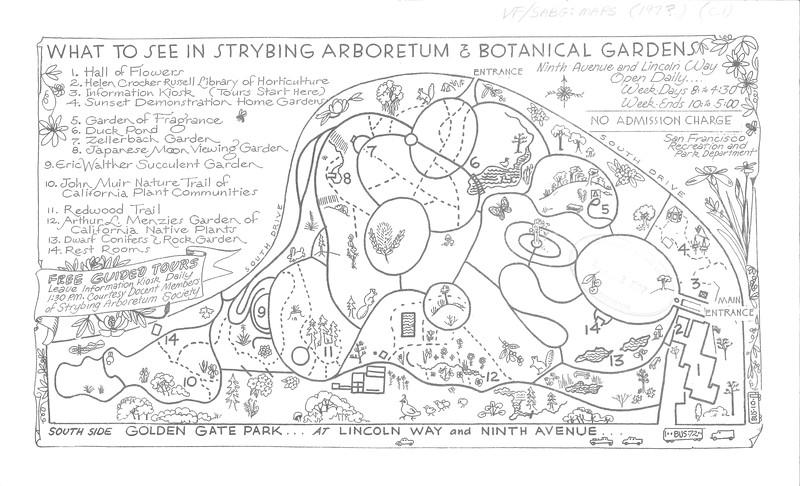

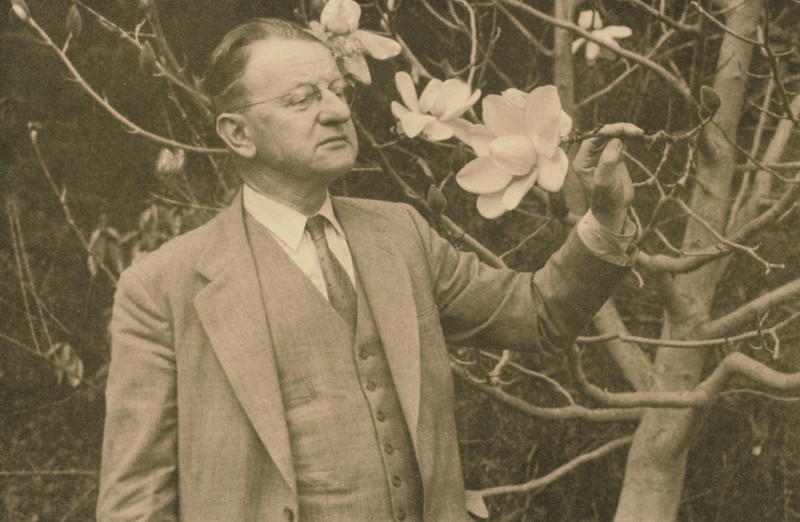

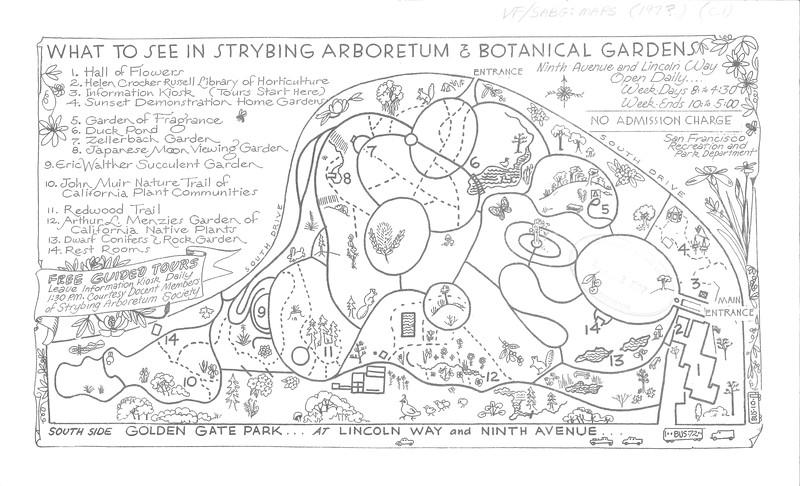

Located in the heart of Golden Gate Park, just blocks away from bustling city life (though not as bustling during these days of the pandemic), the garden is home to an astounding array of more than 9,000 types of flowers, plants and trees from across the globe. When not subject to various levels of quarantine, roughly 400,000 visitors a year tour the grounds, which are open seven days a week and are free to city residents. Horticulturist John McLaren, the Golden Gate Park superintendent for over 50 years, first devised plans for the garden in the late 1800s. But funding problems prevented an official opening until 1940.

Here they can take in velvety pink and magenta flowering magnolias from the Himalayas; endangered South African proteas that grow on a single mountain; and something called a monkey puzzle tree, a rare evergreen from Chile with limbs of sharp, succulent-like leaves unfolding from its trunk. As for native species, the garden hosts everything from California lilac to giant sequoias.

In this 150th year of Golden Gate Park and 80th of the Botanical Garden, the garden has unveiled plans for a brand new nursery to advance its mission of preserving endangered plants increasingly threatened by climate change.

From Big Beach to Big Garden

Staring out at the sanctuary’s lush lawns and winding forested foot trails, it’s hard to imagine this was all once nothing but sand dunes.

Before Golden Gate Park was established in 1870, the dunes stretched out over its thousand-acres, extending east from Ocean Beach, where San Francisco meets the Pacific at the edge of the continent.

“This was just a big dune all the way out. If you dig down 2 feet anywhere here, it’s gonna be sand,” said garden docent Kyle Pierce, while leading a tour in late February, just weeks before the pandemic shut the garden down for several months. It reopened in June, with safety protocols requiring masks and a capacity limit of 2,500 people.

To transform the terrain from beach to garden, he says, the city plowed in horse manure and nutrient-rich soil, so plants could take root and thrive.

“If you amend it enough, you can grow anything,” he said. “By 1879 they’d already planted 150,000 trees.”

Many of the initial Monterey cypress, Monterey pine and blue gum eucalyptus trees remain in the park today, 150 years later. The species were chosen, Pierce says, to serve as a windbreak for other plants to grow.

Preserving Flora From Across the Globe

Over time, the garden has become a refuge for threatened plants from all over the world. One of its main attractions is a collection of more than a hundred different types of magnolia trees, which bloom for three months at the start of each year.

These trees have been dubbed the most significant collection of magnolias for the purposes of conservation outside of China by Botanic Garden Conservation International, a global plant preservation society.

On our walk, Pierce points out the distinct cup-and-saucer arrangement of one magnolia’s pink-hued petals. This Magnolia campbellii, a native to Himalayan valleys, became the first of its kind to blossom in the U.S. back when the garden opened in the winter of 1940.

The rarest tree of the bunch is the Magnolia zenii, or the zen magnolia. Its flowers, snowy white with purple stripes, are smaller and more delicate than the others we passed.

“Only 18 individuals exist in the wild within one province in China, with no sign of regeneration,” Pierce said. “A lot of the garden’s magnolias are wild-collected. So they’re preserving a DNA of wild species.”

The San Francisco Botanical Garden and other created havens for flora play a critical role in protecting plants that are at risk of extinction due to climate change and deforestation.

“Botanical gardens, public gardens, are a key mechanism in making sure those plants don’t disappear from humanity,” said the San Francisco garden’s director, Matthew Stephens. “Because what the research suggests is that they probably won’t be wherever they’re growing now in 150 or 200 years.”

To protect threatened species, he says, the garden partners with greenhouses, nonprofits and governments from around the world. The hope is that preserving a population across a network of different gardens will act as insurance against the extinction of a species in decline.

“The core function of the nursery is to be a pipeline for plants into the garden,” Stephens said. “Through our network of collaborators, new plants arrive at the garden all the time.”

Ethically sourced seeds and seedlings are reared in the greenhouse until they’re hardy enough for planting in the garden outside. Earlier this year, garden officials announced a nearly $7 million project for a new climate-controlled greenhouse and outdoor nursery to replace the current facility, which is more than 50 years old and was originally envisioned as a temporary structure.

“With a new modern nursery,” Stephens said, “it enables us to bring a more sophisticated approach to that new wave, new pipeline of plants for today, but also for future generations.”

From High Altitude Cloud Forests to San Francisco Fog

The successful conservation of rare flora in gardens like this often depends on how well the environment matches the plants’ wild conditions. A species that thrives in San Francisco, for instance, may not do well in Berkeley, even though it’s just across the bay.

“We are blessed with this very cool, foggy, mild climate here in San Francisco,” said garden curator Ryan Guillou. “So we can grow a lot of things that most other gardens can’t.”

In particular, he says, these year-round conditions make the botanical garden a refuge for plants from the cool, high-elevation cloud forests of Africa and South America.

Guillou says less than 1% of the world’s land surface has the right climate to support cloud forest flora, and with climate change, even that small number will decline.

“Their habitat is definitely shrinking because these plants can’t move fast enough up the mountain to stay cool and they’re disappearing,” he said.

A prominent feature of the garden’s Andean Cloud Forest collection are two side-by-side specimens of Ceroxylon quindiuense, or the Andean wax palm. These towering trees grow at elevations higher than any palm species in the world. They’re also the tallest palm trees, growing up to 200 feet in the wild. The bark is chalky white with charcoal-colored rings extending up the trunk, impressions left by falling leaves as the tree grew.

During my visit, I helped Guillou plant another palm species that came to the nursery as a seedling six years ago from the highlands of Colombia. The baby Ceroxylon alpinum, or alpine wax palm, may look like an ordinary house plant now, but Guillou says over the next hundred years it will sprout up 60 feet, and its leaves will develop a glowing silvery sheen.

“These guys are actually one of the more endangered species of the Ceroxylon group,” Guillou said while covering the palm’s roots with soil. “It’s one of the classic examples of species that has to grow here. And if they go extinct in the wild, where else are they going to grow?”

Coping With COVID-19

The three-month coronavirus shutdown cost the Botanical Garden roughly a million dollars in revenue. The garden, which is managed jointly by the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and the San Francisco Botanical Garden Society, laid off 25 staff (12 of whom were hired back upon reopening). Dozens of programs and special events had to be canceled.

But despite the closure, Executive Director Stephanie Linder says plantings and other critical projects have continued, including preparations for the new greenhouse and nursery. Garden officials say plans to break ground on the project in 2021 are still on track.

With the garden now reopened to the public, Linder hopes it can be not only a refuge for plants, but for people who can connect with nature again after being trapped at home for so long.

“We’ve known for quite some time that there is scientific evidence that time spent outdoors in nature boosts immunity, lowers stress hormones, lowers blood pressure, just gives people a sense of well-being, reflection,” Linder said. “And all of those things are needed now more than ever.”

If recent attendance is any indication, Linder is right. The garden welcomed roughly 50,000 visitors in June, a 40 percent jump from last year.

65 epizódok

Manage episode 273561361 series 2486058

Stepping onto the 55-acre grounds of the San Francisco Botanical Garden feels a bit like entering the chocolate room at Willy Wonka’s factory, if that storybook setting were bursting with real plants instead of ones made of candy.

Located in the heart of Golden Gate Park, just blocks away from bustling city life (though not as bustling during these days of the pandemic), the garden is home to an astounding array of more than 9,000 types of flowers, plants and trees from across the globe. When not subject to various levels of quarantine, roughly 400,000 visitors a year tour the grounds, which are open seven days a week and are free to city residents. Horticulturist John McLaren, the Golden Gate Park superintendent for over 50 years, first devised plans for the garden in the late 1800s. But funding problems prevented an official opening until 1940.

Here they can take in velvety pink and magenta flowering magnolias from the Himalayas; endangered South African proteas that grow on a single mountain; and something called a monkey puzzle tree, a rare evergreen from Chile with limbs of sharp, succulent-like leaves unfolding from its trunk. As for native species, the garden hosts everything from California lilac to giant sequoias.

In this 150th year of Golden Gate Park and 80th of the Botanical Garden, the garden has unveiled plans for a brand new nursery to advance its mission of preserving endangered plants increasingly threatened by climate change.

From Big Beach to Big Garden

Staring out at the sanctuary’s lush lawns and winding forested foot trails, it’s hard to imagine this was all once nothing but sand dunes.

Before Golden Gate Park was established in 1870, the dunes stretched out over its thousand-acres, extending east from Ocean Beach, where San Francisco meets the Pacific at the edge of the continent.

“This was just a big dune all the way out. If you dig down 2 feet anywhere here, it’s gonna be sand,” said garden docent Kyle Pierce, while leading a tour in late February, just weeks before the pandemic shut the garden down for several months. It reopened in June, with safety protocols requiring masks and a capacity limit of 2,500 people.

To transform the terrain from beach to garden, he says, the city plowed in horse manure and nutrient-rich soil, so plants could take root and thrive.

“If you amend it enough, you can grow anything,” he said. “By 1879 they’d already planted 150,000 trees.”

Many of the initial Monterey cypress, Monterey pine and blue gum eucalyptus trees remain in the park today, 150 years later. The species were chosen, Pierce says, to serve as a windbreak for other plants to grow.

Preserving Flora From Across the Globe

Over time, the garden has become a refuge for threatened plants from all over the world. One of its main attractions is a collection of more than a hundred different types of magnolia trees, which bloom for three months at the start of each year.

These trees have been dubbed the most significant collection of magnolias for the purposes of conservation outside of China by Botanic Garden Conservation International, a global plant preservation society.

On our walk, Pierce points out the distinct cup-and-saucer arrangement of one magnolia’s pink-hued petals. This Magnolia campbellii, a native to Himalayan valleys, became the first of its kind to blossom in the U.S. back when the garden opened in the winter of 1940.

The rarest tree of the bunch is the Magnolia zenii, or the zen magnolia. Its flowers, snowy white with purple stripes, are smaller and more delicate than the others we passed.

“Only 18 individuals exist in the wild within one province in China, with no sign of regeneration,” Pierce said. “A lot of the garden’s magnolias are wild-collected. So they’re preserving a DNA of wild species.”

The San Francisco Botanical Garden and other created havens for flora play a critical role in protecting plants that are at risk of extinction due to climate change and deforestation.

“Botanical gardens, public gardens, are a key mechanism in making sure those plants don’t disappear from humanity,” said the San Francisco garden’s director, Matthew Stephens. “Because what the research suggests is that they probably won’t be wherever they’re growing now in 150 or 200 years.”

To protect threatened species, he says, the garden partners with greenhouses, nonprofits and governments from around the world. The hope is that preserving a population across a network of different gardens will act as insurance against the extinction of a species in decline.

“The core function of the nursery is to be a pipeline for plants into the garden,” Stephens said. “Through our network of collaborators, new plants arrive at the garden all the time.”

Ethically sourced seeds and seedlings are reared in the greenhouse until they’re hardy enough for planting in the garden outside. Earlier this year, garden officials announced a nearly $7 million project for a new climate-controlled greenhouse and outdoor nursery to replace the current facility, which is more than 50 years old and was originally envisioned as a temporary structure.

“With a new modern nursery,” Stephens said, “it enables us to bring a more sophisticated approach to that new wave, new pipeline of plants for today, but also for future generations.”

From High Altitude Cloud Forests to San Francisco Fog

The successful conservation of rare flora in gardens like this often depends on how well the environment matches the plants’ wild conditions. A species that thrives in San Francisco, for instance, may not do well in Berkeley, even though it’s just across the bay.

“We are blessed with this very cool, foggy, mild climate here in San Francisco,” said garden curator Ryan Guillou. “So we can grow a lot of things that most other gardens can’t.”

In particular, he says, these year-round conditions make the botanical garden a refuge for plants from the cool, high-elevation cloud forests of Africa and South America.

Guillou says less than 1% of the world’s land surface has the right climate to support cloud forest flora, and with climate change, even that small number will decline.

“Their habitat is definitely shrinking because these plants can’t move fast enough up the mountain to stay cool and they’re disappearing,” he said.

A prominent feature of the garden’s Andean Cloud Forest collection are two side-by-side specimens of Ceroxylon quindiuense, or the Andean wax palm. These towering trees grow at elevations higher than any palm species in the world. They’re also the tallest palm trees, growing up to 200 feet in the wild. The bark is chalky white with charcoal-colored rings extending up the trunk, impressions left by falling leaves as the tree grew.

During my visit, I helped Guillou plant another palm species that came to the nursery as a seedling six years ago from the highlands of Colombia. The baby Ceroxylon alpinum, or alpine wax palm, may look like an ordinary house plant now, but Guillou says over the next hundred years it will sprout up 60 feet, and its leaves will develop a glowing silvery sheen.

“These guys are actually one of the more endangered species of the Ceroxylon group,” Guillou said while covering the palm’s roots with soil. “It’s one of the classic examples of species that has to grow here. And if they go extinct in the wild, where else are they going to grow?”

Coping With COVID-19

The three-month coronavirus shutdown cost the Botanical Garden roughly a million dollars in revenue. The garden, which is managed jointly by the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and the San Francisco Botanical Garden Society, laid off 25 staff (12 of whom were hired back upon reopening). Dozens of programs and special events had to be canceled.

But despite the closure, Executive Director Stephanie Linder says plantings and other critical projects have continued, including preparations for the new greenhouse and nursery. Garden officials say plans to break ground on the project in 2021 are still on track.

With the garden now reopened to the public, Linder hopes it can be not only a refuge for plants, but for people who can connect with nature again after being trapped at home for so long.

“We’ve known for quite some time that there is scientific evidence that time spent outdoors in nature boosts immunity, lowers stress hormones, lowers blood pressure, just gives people a sense of well-being, reflection,” Linder said. “And all of those things are needed now more than ever.”

If recent attendance is any indication, Linder is right. The garden welcomed roughly 50,000 visitors in June, a 40 percent jump from last year.

65 epizódok

Minden epizód

×Üdvözlünk a Player FM-nél!

A Player FM lejátszó az internetet böngészi a kiváló minőségű podcastok után, hogy ön élvezhesse azokat. Ez a legjobb podcast-alkalmazás, Androidon, iPhone-on és a weben is működik. Jelentkezzen be az feliratkozások szinkronizálásához az eszközök között.